Ohio-class submarine

Ohio-class SSBN profile

| |

USS Ohio, during her commissioning ceremony in 1981.

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | Ohio class |

| Builders | General Dynamics Electric Boat[1] |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Franklin class |

| Succeeded by | Columbia class[2] |

| Cost | $2 billion (late 1990s)[3] ($3.53 billion in 2023 dollars[4]) |

| Built | 1976–1997 |

| In commission | 1981–present |

| Planned | 24 |

| Completed | 18 |

| Cancelled | 6 |

| Active | 18 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | SSBN/SSGN (hull design SCB-304)[5] |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 560 ft (170 m)[1] |

| Beam | 42 ft (13 m)[1] |

| Draft | 35.5 ft (10.8 m) maximum[6] |

| Propulsion | |

| Speed | |

| Range | Limited only by food supplies |

| Test depth | +800 ft (240 m)[8] |

| Complement | 15 officers, 140 enlisted[1][3] |

| Sensors and processing systems | |

| Armament | 4 × 21 inch (533 mm) Mark 48 torpedo tubes (Forward Compartment 4th level) |

| General characteristics (SSBN-726 to SSBN-733 from construction to refueling) | |

| Armament | 20[a] × Trident I C4 SLBM with up to 8 MIRVed 100 ktTNT W76 nuclear warheads each, range 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) |

| General characteristics (SSBN-734 and subsequent hulls upon construction, SSBN-730 to SSBN-733 since refueling) | |

| Armament | 20[a] × Trident II D5 SLBM with up to 12 MIRVed W76 or W88 (475 ktTNT) nuclear warheads each, range 6,100 nmi (11,300 km; 7,000 mi) |

| General characteristics (SSGN conversion) | |

| Armament | 22 tubes, each with 7 Tomahawk cruise missiles, totaling 154 |

The Ohio class of nuclear-powered submarines includes the United States Navy's 14 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) and its four cruise missile submarines (SSGNs). Each displacing 18,750 tons submerged, the Ohio-class boats are the largest submarines ever built for the U.S. Navy. They are also the third-largest submarines ever built, behind the Russian Navy's Soviet era 48,000-ton Typhoon class, the last of which was retired in 2023,[b][11] and 24,000-ton Borei class.[12] Capable of carrying 24 Trident II missiles apiece, the Ohio class are equipped with just as many missiles as, if not more than, either the Borei class (16) or the deactivated Typhoon class (20).

Like their predecessors the Benjamin Franklin and Lafayette classes,[13] the Ohio-class SSBNs are part of the United States' nuclear-deterrent triad, along with U.S. Air Force strategic bombers and intercontinental ballistic missiles.[14] The 14 SSBNs together carry about half of U.S. active strategic thermonuclear warheads. Although the Trident missiles have no preset targets when the submarines go on patrol,[15]: 392 they can be given targets quickly, from the United States Strategic Command based in Nebraska,[16] using secure and constant radio communications links, including very low frequency systems.

All the Ohio-class submarines, except for USS Henry M. Jackson, are named for U.S. states, which U.S. Navy tradition had previously reserved for battleships and later cruisers. The Ohio class is to be gradually replaced by the Columbia class beginning in 2031.

Description

[edit]The Ohio-class submarine was designed for extended strategic deterrent patrols. Each submarine is assigned two complete crews, called the Blue crew and the Gold crew, each typically serving 70-to-90-day deterrent patrols. To decrease the time in port for crew turnover and replenishment, three large logistics hatches have been installed to provide large-diameter resupply and repair access. These hatches allow rapid transfer of supply pallets, equipment replacement modules, and machinery components, speeding up replenishment and maintenance of the submarines. Moreover, the "stealth" ability of the submarines was significantly improved over all previous ballistic-missile subs. Ohio was virtually undetectable in her sea trials in 1982, giving the U.S. Navy extremely advanced flexibility.[17]

The class's design allows the boat to operate for about 15 years between major overhauls. These submarines are reported to be as quiet at their cruising speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) or more as the previous Lafayette-class submarines at 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph), although exact information remains classified.[18] Fire control for their Mark 48 torpedoes is carried out by Mark 118 Mod 2 system,[9] while the Missile Fire Control system is a Mark 98.[9]

The Ohio-class submarines were constructed from sections of hull, with each four-deck section being 42 ft (13 m) in diameter.[6][9] The sections were produced at the General Dynamics Electric Boat facility, Quonset Point, Rhode Island, and then assembled at its shipyard at Groton, Connecticut.[6]

The US Navy has a total of 18 Ohio-class submarines which consist of 14 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), and four cruise missile submarines (SSGNs). The SSBN submarines provide the sea-based leg of the U.S. nuclear triad. Each SSBN submarine is armed with up to 20 Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). Each SSGN is capable of carrying 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles, plus a complement of Harpoon missiles to be fired through their torpedo tubes.

History

[edit]The Ohio class was designed in the 1970s to carry the concurrently designed Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile. The first eight Ohio-class submarines were armed at first with 24 Trident I C4 SLBMs.[6] Beginning with the ninth Trident submarine, Tennessee, the remaining boats were equipped with the larger, three-stage Trident II D5 missile.[9] The Trident I missile carries eight multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles, while the Trident II missile carries 12, in total delivering more destructive power than the Trident I missile and with greater accuracy. Starting with Alaska in 2000, the Navy began converting its remaining ballistic missile submarines armed with C4 missiles to carry D5 missiles. This task was completed in mid-2008. The first eight submarines had their home ports at Bangor, Washington, to replace the submarines carrying Polaris A3 missiles that were then being decommissioned. The remaining 10 submarines originally had their home ports at Kings Bay, Georgia, replacing the Poseidon and Trident Backfit submarines of the Atlantic Fleet.

SSBN/SSGN conversions

[edit]

In 1994, the Nuclear Posture Review study determined that, of the 18 Ohio SSBNs the U.S. Navy would be operating in total, 14 would be sufficient for the strategic needs of the U.S. The decision was made to convert four Ohio-class boats into SSGNs capable of conducting conventional land attack and special operations. As a result, the four oldest boats of the class—Ohio, Michigan, Florida, and Georgia—progressively entered the conversion process in late 2002 and were returned to active service by 2008.[19] The boats could thereafter carry 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles and 66 special operations personnel, among other capabilities and upgrades.[19] The cost to refit the four boats was around US$1 billion (2008 dollars) per vessel.[20] During the conversion of these four submarines to SSGNs (see below), five of the remaining submarines, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Nebraska, Maine, and Louisiana, were transferred from Kings Bay to Bangor.[citation needed] Further transfers occur as the strategic weapons goals of the United States change.

In 2011, Ohio-class submarines carried out 28 deterrent patrols. Each patrol lasts around 70 days. Four boats are on station ("hard alert") in designated patrol areas at any given time.[21] From January to June 2014, Pennsylvania carried out a 140-day-long patrol, the longest to date.[22]

The conversion modified 22 of the 24 88-inch (2.2 m) diameter Trident missile tubes to contain large vertical launch systems, one configuration of which may be a cluster of seven Tomahawk cruise missiles. In this configuration, the number of cruise missiles carried could be a maximum of 154, the equivalent of what is typically deployed in a surface battle group. Other payload possibilities include new generations of supersonic and hypersonic cruise missiles, and Submarine Launched Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles,[citation needed] unmanned aerial vehicles, the ADM-160 MALD, sensors for antisubmarine warfare or intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions, counter mine warfare payloads such as the AN/BLQ-11 Long Term Mine Reconnaissance System, and the broaching universal buoyant launcher and stealthy affordable capsule system specialized payload canisters.[citation needed]

The missile tubes also have room for stowage canisters that can extend the forward deployment time for special forces. The other two Trident tubes are converted to swimmer lockout chambers. For special operations, the Dry Combat Submersible (which replaced the Advanced SEAL Delivery System), as well as the dry deck shelter, can be mounted on the lockout chamber and the boat will be able to host up to 66 special-operations sailors or Marines, such as Navy SEALs, or USMC MARSOC teams. Improved communications equipment installed during the upgrade allows the SSGNs to serve as a forward-deployed, clandestine Small Combatant Joint Command Center.[23]

On 26 September 2002, the Navy awarded General Dynamics Electric Boat a US$442.9 million contract to begin the first phase of the SSGN submarine conversion program. Those funds covered only the initial phase of conversion for the first two boats on the schedule. Advance procurement was funded at $355 million in fiscal year 2002, $825 million in the FY 2003 budget and, through the five-year defense budget plan, at $936 million in FY 2004, $505 million in FY 2005, and $170 million in FY 2006. Thus, the total cost to refit the four boats is just under $700 million per vessel.[citation needed]

In November 2002, Ohio entered a dry-dock, beginning her 36-month refueling and missile-conversion overhaul. Electric Boat announced on 9 January 2006 that the conversion had been completed. The converted Ohio rejoined the fleet in February 2006, followed by Florida in April 2006. The converted Michigan was delivered in November 2006. The converted Ohio went to sea for the first time in October 2007. Georgia returned to the fleet in March 2008 at Kings Bay.[24][failed verification] These four SSGNs are expected to remain in service until about 2023–2026. At that point, their capabilities will be replaced with Virginia Payload Module-equipped Virginia-class submarine.[25]

Missile tube reduction

[edit]As part of the New START treaty, four tubes on each SSBN were deactivated in 2017, reducing the number of missiles to 20 per boat.[26]

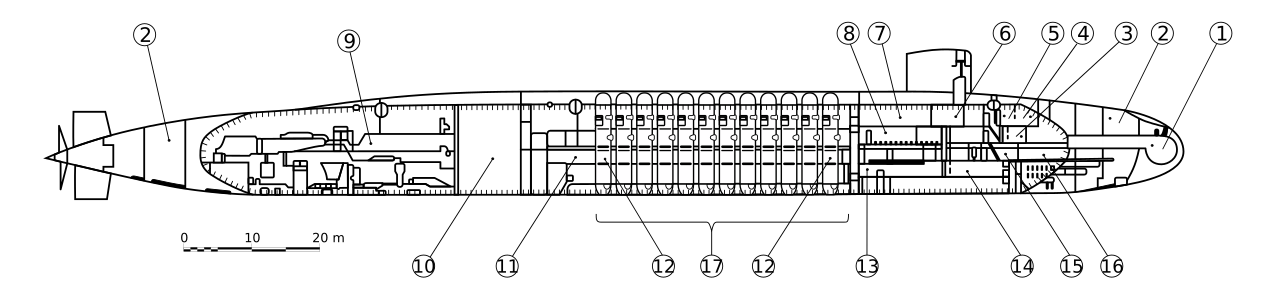

Detailed cross-section

[edit]Boats in class

[edit]| Boat | Hull number | Ordered | Laid down | Launched | Delivered | Commissioned | Decommissioned | Homeport | Service life (status) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guided-missile submarines (SSGN) | ||||||||||

| Ohio | SSGN-726 | 1 July 1974 | 10 April 1976 | 7 April 1979 | 28 October 1981 | 11 November 1981 | Proposed 2026[27] | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 43 years, 1 month and 21 days (in active service) |

[28] |

| Michigan | SSGN-727 | 28 February 1975 | 4 April 1977 | 26 April 1980 | 28 August 1982 | 11 September 1982 | Proposed 2028[29] | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 42 years, 3 months and 21 days (in active service) |

[30] |

| Florida | SSGN-728 | 28 February 1975 | 19 January 1981 | 14 November 1981 | 17 May 1983 | 18 June 1983 | Proposed 2026[31] | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 41 years, 6 months and 14 days (in active service) |

[32] |

| Georgia | SSGN-729 | 20 February 1976 | 7 April 1979 | 6 November 1982 | 17 January 1984 | 11 February 1984 | Proposed 2028[33] | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 40 years, 10 months and 21 days (in active service) |

[34] |

| Ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) | ||||||||||

| Henry M. Jackson (ex Rhode Island) |

SSBN-730 | 6 June 1977 | 19 November 1981 | 15 October 1983 | 11 September 1984 | 6 October 1984 | Proposed 2027[35] | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 40 years, 2 months and 26 days (in active service) |

[36] |

| Alabama | SSBN-731 | 27 February 1978 | 27 August 1981 | 19 May 1984 | 23 April 1985 | 25 May 1985 | Proposed 2028[37] | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 39 years, 7 months and 7 days (in active service) |

[38] |

| Alaska | SSBN-732 | 27 February 1978 | 9 March 1983 | 12 January 1985 | 26 November 1985 | 25 January 1986 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 38 years, 11 months and 7 days (in active service) |

[39] | |

| Nevada | SSBN-733 | 7 January 1981 | 8 August 1983 | 14 September 1985 | 7 August 1986 | 16 August 1986 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 38 years, 4 months and 16 days (in active service) |

[40] | |

| Tennessee | SSBN-734 | 7 January 1982 | 9 June 1986 | 13 December 1986 | 18 November 1988 | 17 December 1988 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 36 years and 15 days (in active service) |

[41] | |

| Pennsylvania | SSBN-735 | 29 November 1982 | 2 March 1987 | 23 April 1988 | 22 August 1989 | 9 September 1989 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 35 years, 3 months and 23 days (in active service) |

[42] | |

| West Virginia | SSBN-736 | 21 November 1983 | 18 December 1987 | 14 October 1989 | 10 September 1990 | 20 October 1990 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 34 years, 2 months and 12 days (in active service) |

[43] | |

| Kentucky | SSBN-737 | 13 August 1985 | 18 December 1987 | 11 August 1990 | 27 June 1991 | 13 July 1991 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 33 years, 5 months and 19 days (in active service) |

[44] | |

| Maryland | SSBN-738 | 14 March 1986 | 22 April 1986 | 10 August 1991 | 31 May 1992 | 13 June 1992 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 32 years, 6 months and 19 days (in active service) |

[45] | |

| Nebraska | SSBN-739 | 26 May 1987 | 6 July 1987 | 15 August 1992 | 18 June 1993 | 10 July 1993 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 31 years, 5 months and 22 days (in active service) |

[46] | |

| Rhode Island | SSBN-740 | 15 January 1988 | 15 September 1988 | 17 July 1993 | 22 June 1994 | 9 July 1994 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 30 years, 5 months and 23 days (in active service) |

[47] | |

| Maine | SSBN-741 | 5 October 1988 | 3 July 1990 | 16 July 1994 | 21 June 1995 | 29 July 1995 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 29 years, 5 months and 13 days (in active service) |

[48] | |

| Wyoming | SSBN-742 | 18 October 1989 | 8 August 1991 | 15 July 1995 | 20 June 1996 | 13 July 1996 | Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia | 28 years, 5 months and 19 days (in active service) |

[49] | |

| Louisiana | SSBN-743 | 19 December 1990 | 23 October 1992 | 27 July 1996 | 14 August 1997 | 6 September 1997 | Naval Base Kitsap, Washington | 27 years, 3 months and 26 days (in active service) |

[50] | |

Note: Boats based at Naval Base Kitsap, Washington are operated by the U.S. Pacific Fleet, while boats based at Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia are operated by U.S. Fleet Forces Command, (formerly the U.S. Atlantic Fleet).

Replacement

[edit]The U.S. Department of Defense anticipated a continued need for a sea-based strategic nuclear force.[citation needed] The first of the current Ohio-class SSBNs was expected to be retired by 2029,[citation needed] so the replacement submarine would need to be seaworthy by that time. A replacement was expected to cost over $4 billion per unit compared to Ohio's $2 billion.[3] The U.S. Navy explored two options. The first option was a variant of the Virginia-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. The second option was a dedicated SSBN, either with a new hull or based on an overhaul of the current Ohio class.[citation needed]

With the cooperation of both Electric Boat and Newport News Shipbuilding, in 2007, the U.S. Navy began a cost-control study.[citation needed] Then in December 2008, the U.S. Navy awarded Electric Boat a contract for the missile compartment design of the Ohio-class replacement, worth up to $592 million. Newport News is expected to receive close to 4% of that project. In April 2009, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates stated that the U.S. Navy was expected to begin such a program in 2010.[3] The new vessel was scheduled to enter the design phase by 2014. If a new hull design was to be used, the program needed to be initiated by 2016 to meet the 2029 deadline.[citation needed][needs update]

The Columbia class was officially designated on 14 December 2016, by Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, and the lead submarine will be USS District of Columbia (SSBN-826).[51] The Navy wants to procure the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021,[52] though it is not expected to enter service until 2031.[53][54]

In 2020, Navy officials first publicly discussed the idea of extending the lives of select Ohio-class boats at the Naval Submarine League's 2020 conference. During the 2022 conference, Rear Admiral Scott Pappano, the program executive officer for strategic submarines, and Rear Admiral Douglas G. Perry, the director of undersea warfare on the Chief of Naval Operations' staff, discussed the Columbia-class program, and also touched on the possibility of finding Ohio-class boats that had sufficient remaining nuclear fuel and were in good enough material state to be given a further extension to their lives.[55]

In popular culture

[edit]As ballistic-missile submarines, the Ohio class has occasionally been portrayed in fiction books and films.

- Tom Clancy wrote Ohio-class submarines into several novels,[56] such as USS Maine (SSBN-741) in The Sum of All Fears (1991).[57]

- The fictional USS Montana is featured in the 1989 film The Abyss.[58]

- USS Alabama is the setting for the 1995 submarine film Crimson Tide.[59]

- The fictional ballistic missile submarine USS Colorado (SSBN-753) is the primary setting for the ABC television series Last Resort.[60]

- USS Wyoming is featured in Season 1, Episode 13 of the American television series The Brave.[61]

See also

[edit]- List of submarine classes of the United States Navy

- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of submarine classes in service

- Submarines in the United States Navy

- Submarine-launched ballistic missile

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Each hull initially started out with 24 missile tubes. This number was reduced to 20 in 2017 due to the New START treaty

- ^ The last boat of the Typhoon class, Dmitriy Donskoi, was confirmed by Russia, in February 2023, as deactivated.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Ohio-class SSGN-726 Overview". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "New U.S. Navy Nuclear Sub Class to Be Named for D.C." 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Frost, Peter. "Newport News contract awarded". Daily Press. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 November 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Adcock, Al. (1993). U.S. Ballistic Missile Submarines. Carrolltown, Texas: Squadron Signal. pp. 4, 40. ISBN 978-0-89747-293-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Adcock, Al (1993). U.S. Ballistic Missile Submarines. Carrolltown, Texas: Squadron Signal. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-89747-293-7.

- ^ "Part II.6 Trident". Appendices: Commission on the Organization of the Government for the Conduct of Foreign Policy. Vol. IV: Appendix K: Adequacy of Current Organization: Defense and Arms Control. U.S. Government Printing Office. June 1975. pp. 177–179. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

The projected boat would have a 30,000 ton displacement and would be powered by two 30,000 shp reactors... ...both the submarine and the missile grew incrementally in size to their current dimensions — the missile by six inches in diameter and four to five feet in length; the submarine by 5,000 shp in reactor output...

- ^ "How deep can a submarine dive?". navalpost.com. 26 April 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adcock, Al (1993). U.S. Ballistic Missile Submarines. Carrolltown, Texas: Squadron Signal. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-89747-293-7.

- ^ Cole, Brendan (6 February 2023). "Russia loses world's largest nuclear submarine". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "941 Typhoon". Federation of American Scientists. Fas.org. 25 August 2000. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "935 Borei". Federation of American Scientists. Fas.org. 13 July 2000. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ Chant 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Chinworth 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Croddy, Eric A.; Wirtz, James J., eds. (2005). Weapons of Mass Destruction: Nuclear weapons. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-490-5.

- ^ Genat & Genat 1997, p. 39.

- ^ D. Douglas Dalgleish and Larry Schweikart, Trident. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. 1984.

- ^ Lee, T. W. (30 December 2008). Military Technologies of the World [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-275-99536-2.

- ^ a b "Guided Missile Submarines – SSGN". U.S. Navy. Navy.mil. 10 November 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (22 May 2008). "Navy Trident Submarine Conversion (SSGN) Program: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2012 – via Fas.org.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M. (December 2012). "Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces Special Report No 5" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Arendes, Ahron (30 June 2014). "USS Pennsylvania Sets Patrol Record". Military.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "USS Ohio Returns To Service As Navy's First SSGN" (PDF). Electric Boat News (Newsletter). General Dynamics Electric Boat. February 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2009.

- ^ "Navy Marks USS Georgia's Return To Service". CBS 4 News Jacksonville. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ O'Rourke, Ronald (1 March 2012). "CRS-RL32418 Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress". Open CRS. Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 17 December 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen (13 January 2018). "New Data Shows Detail About Final Phase of US New START Treaty Reductions". fas.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Ohio (SSGN 726)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Michigan (SSGN 727)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 24 February 2006. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Florida (SSGN 728)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Georgia (SSGN 729)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 17 December 2007. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN 730)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025" (PDF). media.defense.gov. March 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ "USS Alabama (SSBN 731)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Alaska (SSBN 732)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Nevada (SSBN 733)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Tennessee (SSBN 734)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 23 August 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Pennsylvania (SSBN 735)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS West Virginia (SSBN 736)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Kentucky (SSBN 737)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Maryland (SSBN 738)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Nebraska (SSBN 739)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Rhode Island (SSBN 740)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Maine (SSBN 741)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 23 August 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Wyoming (SSBN 742)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 23 August 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "USS Louisiana (SSBN 743)". Naval Vessel Register. Navy.mil. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- ^ "SECNAV Mabus to Officially Designate First ORP Boat USS Columbia (SSBN-826)". USNI News. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Report on the Columbia-class Nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarine Program". USNI News. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "Nuclear Posture Review - Final Report" (PDF). media.defense.gov. February 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "SENEDIA Defense Innovation Days" (PDF). Senedia.org. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ "US Navy wants to avoid shortfall of nuke-armed subs in 2030s". defensenews.com. 2 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Terdoslavich, William (2006). The Jack Ryan Agenda: Policy and Politics in the Novels of Tom Clancy: An Unauthorized Analysis. Forge Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-7653-1248-4.

- ^ Akers, Greg. "More patriot games played in Jack Ryan". Memphis Flyer. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Usnavymuseum.org" (PDF). www.usnavymuseum.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "Crimson Tide". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ "Last Resort Co-Creator Explains Submarine Story Development". The Dead Bolt. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Roots, Kimberly (29 January 2018). "The Brave Finale Recap: Man Down!". TVLine. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chant, Chris (2005). Submarine Warfare Today. Leicester, United Kingdom: Silverdale Books. ISBN 1-84509-158-2. OCLC 156749009.

- Chinworth, William C. (15 March 2006). The Future of the Ohio Class Submarine (PDF) (Master of Strategic Studies thesis). Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania: U.S. Army War College. OCLC 70852911.

- Genat, Robert; Genat, Robin (1997). Modern U.S. Navy Submarines. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International. ISBN 0-7603-0276-6. OCLC 36713050.

Further reading

[edit]- Dalgleish, D. Douglas; Schweikart, Larry (1984). Trident. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Hutchinson, Robert (2006). Jane's Submarines War Beneath the Waves: From 1776 to the Present Day. New Line Books. ISBN 978-1-59764-181-4.

- O'Rourke, Ronald. "Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service – via Every CRS Report.